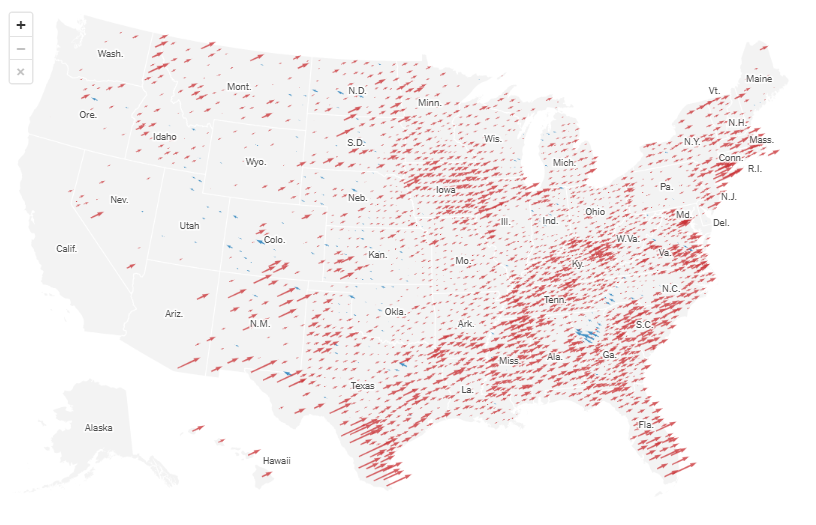

Shift in margin:

Compared with 2020, presidential vote

in places that have reported almost all of their votes.

The Ecological Fallacy: This map does not depict individual voters who have shifted to the GOP; rather, it illustrates the counties where the electorate has moved away from the Democratic Party.

The Fact: The electorate, or voter turnout, represents only a fraction of the eligible voting population. In the United States, approximately two-thirds of eligible voters participate in presidential elections, while turnout drops to around half for midterm elections.

The Question: What truly reflects the will of “the people,” that is, the voting-eligible population? Only a comprehensive census can provide an answer to this question. Elections capture merely a fraction of the total population, and, like any poll, it is crucial to identify selection bias to evaluate its representativeness.

We do now that the nonvoting but eligible population is more disengaged from the political process. It may also be that they decide not to vote objecting specific policies, like the “uncommitted” ballots in the Democratic primaries to object US policies in the Middle East.

Polling data often describes the nonvoting or “low propensity” (unlikely) voters as a diverse group with certain common characteristics. These individuals are generally younger, less educated, and have lower income levels compared to typical voters. This group, which includes a higher percentage of racial and ethnic minorities, also tend to participate less in midterm elections than in presidential ones. Additionally, these voters often feel disconnected from the political process, believing that their vote does not matter or that the system does not represent their interests.

An Answer: Rather than viewing the outcome of the 2024 presidential election as a shift to the right, it may be more insightful to examine how selectively motivating unlikely voters to participate in the political process influences election results.

To be continued (as the full results of the 2024 US presidential elections come in).

Super PACs can influence election outcomes by strategically targeting non-representative segments of the vote-eligible but regularly non-voting population in several ways:

- Micro-Targeting: Using sophisticated data analytics, Super PACs can identify specific demographics or communities that typically do not vote but might be swayed by particular issues. By tailoring messages that resonate with these groups, they can mobilize them to vote in a way that aligns with the Super PAC’s agenda.

- Issue-Based Campaigns: By focusing on niche issues that are highly relevant to certain non-voting segments, Super PACs can create a sense of urgency or importance around voting. This might involve highlighting local concerns or specific policy changes that directly impact these communities.

- Emotional Appeals: Super PACs can use emotionally charged advertisements to evoke strong reactions, such as fear or hope, which can motivate previously apathetic voters to participate. These ads often focus on controversial or polarizing topics to drive engagement.

- Disinformation Campaigns: In some cases, Super PACs might spread misleading or false information to confuse or mislead certain voter segments. This can either mobilize them to vote based on incorrect information or demobilize them by creating distrust in the electoral process.

- Voter Suppression Tactics: While not directly a method of mobilizing non-voters, Super PACs might support efforts that indirectly suppress the vote of opposing demographics, thereby amplifying the impact of newly mobilized voters.

By focusing on these strategies, money (Super PACs) can skew election outcomes by activating specific segments of the population that do not typically participate, thereby altering the representative nature of the election results.

Discover more from Hierarchical Democracy

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

One thought on “The Red Wave Mirage”