The Nature of Power in National and World Affairs

Power, at its core, is the ability to influence outcomes—shaping decisions, behaviors, and the systems that govern our world. It operates not only in visible, quantifiable forms, such as political control or military strength, but also through intangible forces like cultural influence and moral authority. To understand the complex dynamics of power in national and global contexts, we can categorize it broadly into Tangible (Material) Power and Ideational Power, recognizing the interplay between these forces and their mediation by structural systems.

Tangible (Material) Power

Material power consists of visible, concrete resources that shape geopolitics and state influence. These include political authority, financial might, military strength, and, increasingly, technological innovation. Together, these drivers form the basis of hard power—the ability to compel compliance or assert dominance.

Political Power

Political power resides in the machinery of governance and diplomacy, influencing societies within and beyond borders. Institutions like governments, alliances, and international organizations channel this influence. For instance, NATO exemplifies political power’s cooperative potential, coordinating its member states for defense and global stability. Domestically, strong political leadership often determines a nation’s standing on the world stage.

Financial Power

Financial strength, rooted in resources like trade, investment, and economic systems, enables states to project influence without direct coercion. The United States’ control of the global financial system, particularly through the dominance of the dollar, demonstrates how financial power can shape international policy. Similarly, China’s Belt and Road Initiative leverages infrastructure investment to expand its sway across Asia, Africa, and beyond.

Military Power

For centuries, military power has underscored state dominance. Strong armed forces and advanced weaponry deter aggression and enforce political agendas. A modern example is Russia’s annexation of Crimea, which showcased how military might can alter borders. However, in an era of interconnected global systems, excessive reliance on military force often invites counterproductive consequences, such as international sanctions or loss of moral credibility.

Technological Power

Technological advancements now redefine the boundaries of material power. From artificial intelligence to cybersecurity, the ability to innovate and control technological ecosystems has emerged as a decisive factor in global influence. For instance, cyberattacks have become tools of warfare, enabling states to destabilize rivals without direct physical confrontation. Countries with cutting-edge tech industries, like the U.S. and China, are setting new paradigms for global power through competition in AI and quantum computing.

Ideational Power

While material power influences through force or economic leverage, ideational power derives from shared values, principles, and perceptions. This includes moral authority, cultural influence, and intellectual leadership, often referred to collectively as forms of soft power.

Moral Authority

Moral authority stems from adherence to justice, human rights, and ethical leadership. Figures like Nelson Mandela demonstrated how moral authority can galvanize change, even in the absence of material power. On a global scale, institutions like the United Nations derive their legitimacy from their moral mission, advocating for peace, development, and human dignity.

Cultural Influence

Culture shapes perceptions and norms, permeating societies in ways that transcend borders. The export of films, music, education, and values constitutes a profound form of influence. Hollywood’s global dominance, for example, has long bolstered the United States’ soft power by embedding its cultural ideals into foreign societies. Similarly, Japan has leveraged its cultural exports—anime, technology, and cuisine—to elevate its international reputation.

Intellectual Leadership

Thought leadership, rooted in universities, think tanks, and innovation hubs, molds ideologies and policy on a global scale. Nations that nurture intellectual excellence often dominate discourse and decision-making. Countries like Germany, known for technological and environmental advancements, and the U.S., home to many of the world’s leading universities, define how intellectual leadership amplifies a nation’s global standing.

Interactions Between Material and Ideational Power

Power rarely operates in isolation. Instead, its material and ideational dimensions interact, creating feedback loops and dynamic shifts. For example, Ukraine’s resistance to Russian aggression exemplifies the convergence of these forces. While Ukraine leverages Western military and financial assistance (material power), its moral authority and global support stem from the soft power of its struggle for sovereignty and self-determination. Similarly, a nation like South Korea demonstrates ideational power through cultural exports while using technological innovation to strengthen its material power.

Technology often amplifies the connections between these forces. Social media platforms, for instance, propagate ideational messages, enabling leaders and movements to wield soft power on a global scale. Grassroots environmental campaigns highlight how cultural and moral influence challenge traditional material power structures, such as corporations and states denying climate action.

Structural and Systemic Power

Structural power governs how material and ideational forces are distributed and mediated through global systems. Institutions like the United Nations, the World Trade Organization, and the World Bank shape the operations of power at a systemic level, influencing rules, norms, and resource allocation. For example, sanctions imposed by the UN Security Council represent collective political, military, and moral will, effectively constraining rogue states.

Structural power can also entrench inequalities, as seen in the disproportionate influence of powerful nations in global decision-making. At the same time, these systems offer avenues for smaller states or non-state actors to amplify their voices, as demonstrated by climate accords that give platforms to vulnerable nations.

Challenges and Future Trends in Power

Modern power dynamics are increasingly complex and fluid. Measuring power is difficult because ideational influence, though intangible, can sometimes outweigh material force. Grassroots movements, like Greta Thunberg’s climate activism, show how moral authority and cultural resonance challenge traditional notions of power. Similarly, as technology democratizes access to information, centralized states face challenges from decentralized forces like blockchain or social media-driven activism.

Looking ahead, technological advancement will remain pivotal. The race for AI supremacy or control over resources like rare earth metals will likely shape material power. Conversely, cultural globalization and multipolarity will redefine ideational influence, with emerging nations like India and Brazil gaining prominence on the world stage.

Conclusion

Power is a multifaceted phenomenon, encompassing both tangible material resources and intangible ideational forces. Understanding its operation requires exploring how these categories interact and are shaped by global structures. Tangible dimensions like political, financial, military, and technological power are indispensable in enforcing influence, yet often rely on ideational dimensions like moral authority, cultural influence, and intellectual leadership to sustain legitimacy and long-term impact.

To adapt to changing power dynamics, nations and actors must learn to balance hard and soft power, ensuring that material strength aligns with values and principles. Ultimately, the interplay of these forces determines the contours of influence in a world increasingly defined by interdependence, innovation, and the demand for justice.

Purpose in the Use of Power

Power does not operate in a moral vacuum. Its legitimacy and effectiveness are deeply influenced by the purpose — good or bad — for which it is wielded. At its core, power can be directed toward the common good—advancing justice, peace, and equity—or it can be driven by narrow, self-serving interests that prioritize national, corporate, or individual gain at the expense of broader humanity. The purpose behind wielding power significantly influences its ethical implications and the legitimacy of its outcomes.

Power for the Common Good

When power is wielded altruistically, it often seeks to address systemic challenges, improve human well-being, and foster cooperation. One example of such use is the global effort to eradicate diseases through initiatives like the World Health Organization’s campaigns against polio and malaria. Here, financial, political, and technological resources converge with moral authority to achieve a purpose greater than any single nation’s interest.

Similarly, Norway’s leadership in peace negotiations, such as its role in mediating the Oslo Accords, illustrates how diplomatic power can serve the cause of conflict resolution and peacebuilding. Such acts of altruism boost a nation’s or institution’s moral authority, making their influence more enduring and respected across borders.

Selfish & Nationalistic Wielding of Power

Conversely, power is often used to further self-serving or nationalistic goals, sometimes at the expense of global harmony. Corporate lobbying in international policy, for example, highlights how financial and political power can be directed toward maximizing private profits rather than collective benefit. The fossil fuel industry’s influence in slowing climate change legislation demonstrates how self-interested power can perpetuate environmental harm for economic gain.

On a national level, examples abound of power wielded for dominance rather than justice. Colonialism and resource exploitation by imperial powers, like the British extraction of wealth from India, serve as stark reminders of how power driven by selfish purposes can devastate societies and economies. Modern parallels include land grabs and economic coercion through debt-trap diplomacy, where material power is wielded for geopolitical leverage rather than mutual benefit.

Ethical Implications

The purpose behind power shapes its ethical landscape. Power for the common good fosters shared trust and connects material and ideational dimensions in ways that align with global values. Conversely, selfish uses of power unravel cooperation and often lead to resistance or retaliation. For example, the moral authority of the United States as a global leader has been eroded in instances where military interventions—such as the Iraq War—were perceived as aligned more with strategic interests than humanitarian principles.

The ethical implications of purpose are also evident in the perception of soft power. Cultural exports, when seen as tools of domination rather than cultural exchange, can provoke backlash. This is evidenced in the criticism of Western media homogenization, which some argue erodes local traditions and identities.

The Impact of Purpose on Legitimacy and Effectiveness

The purpose behind power strongly influences its legitimacy. Power wielded altruistically garners not only global support but also long-term trust. For instance, institutions like Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders) gain their influence not from material resources but from the clear moral purpose of their actions. This inspires collaboration and amplifies the impact of their efforts.

On the other hand, self-serving uses of power often lead to diminished effectiveness over time. Military occupations driven by resource extraction or geopolitical gain frequently face insurgency and instability, as seen in the prolonged conflicts in Afghanistan. Similarly, economic sanctions imposed without moral justification or global consensus can engender resistance from affected nations and weaken multilateral frameworks.

Purpose and the Interplay of Power Dimensions

The purpose behind power links material and ideational elements, shaping their interplay. A nation investing in renewable energy not only leverages material power (technological advancements and economic capital) but also strengthens its ideational influence by aligning with global sustainability goals. Germany’s Energiewende, or energy transition, showcases how purpose can unify tangible and intangible powers to build both credibility and impact.

Conversely, when technological or military power is wielded selfishly (“might makes right”) , the repercussions can undermine soft power. A country pioneering artificial intelligence solely to control or surveil others risks alienating partners and motivating counterbalancing strategies. Purpose, therefore, acts as a guiding force, determining whether power reinforces its own legitimacy or undermines it by eroding trust and cooperation.

In the context of power dynamics, the phrase “might makes right” suggests that those with power or strength can impose their will and determine what is considered right or just, often regardless of ethical considerations. It implies that power itself justifies actions, meaning that those who are stronger or more powerful can dictate terms and outcomes, often sidelining moral or ethical standards. This concept promotes a worldview where force and coercion override justice and fairness.

Shaping Perceptions and Global Outcomes

Purpose is the lens through which the world judges power, influencing global perceptions and outcomes. Nations or organizations that align their power with universally recognized moral values often leave lasting positive legacies. Conversely, the pursuit of power for narrow, self-serving motives risks deteriorating relationships and fostering conflict.

The evolving landscape of international affairs necessitates that power, in all its forms, engages with the pressing questions of purpose. Whether addressing climate change, alleviating inequality, or resolving conflicts, the intent behind power determines not just outcomes but also the survival of trust and cooperation essential in an interdependent world. Power, when wielded wisely and ethically, has the potential to transcend its own definition—becoming a force not just for influence, but for humanity’s collective good.

Israel’s Military Actions in Gaza

Israel’s recent military actions in Gaza offer a stark example of how the use of power can reflect contentious purposes and provoke global debate. These actions have been criticized by various international organizations, governments, and human rights groups for violating international law, such as excessive use of force, targeting civilian infrastructure, and contributing to widespread humanitarian suffering. Such measures raise questions about whether the purpose behind this use of power aligns with ethical principles or instead serves narrower, self-serving goals.

From Israel’s perspective, these actions are often justified through the lens of national security. Its leaders cite the need to neutralize militant threats, protect citizens, and maintain the country’s territorial integrity. Supporters argue that a state has not only the right but the obligation to defend itself, particularly in the face of ongoing rocket attacks and other forms of aggression. This perspective underscores a purpose aimed at ensuring survival and security in a hostile regional environment.

However, the proportionality and intent of these military campaigns is questionable. The actions have exacerbated an already dire humanitarian crisis in Gaza, displaced countless civilians, and undermined prospects for peace by hardening divisions. Violations of international norms—such as the targeting of densely populated areas or restricting essential aid—point to morally-flawed political or ideological goals driving these operations, such as consolidating control or undermining Palestinian autonomy, rather than fostering long-term security or coexistence. This casts doubt on whether the purpose aligns with principles of justice, equity, and global responsibility.

This situation underscores the broader interplay between power, purpose, and perception. For power to maintain global credibility, its application must not only achieve its objectives but also reflect a purpose that others deem just. Otherwise, it risks alienating allies, damaging reputations, and perpetuating cycles of conflict, thus failing to secure any sustainable, meaningful resolution.

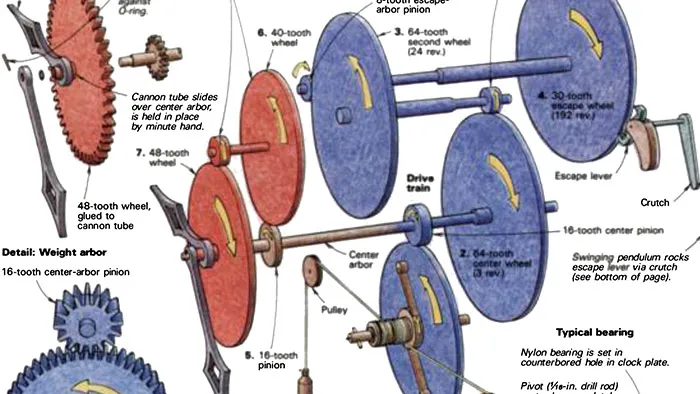

Political Power and Physics

Political power and physical power share foundational parallels—similar in structure, yet distinct in their execution. The physics definition of power as energy over time offers a metaphorical lens to interpret the nature and dynamics of power in politics. Each term within this definition carries weight when applied to political contexts, illuminating the intricacies of influence, capacity, and effect.

Energy as Capacity to Do Work

In physics, energy represents the potential to create change, achieved through work. Politically, energy can be seen as the resources, strategies, and will a leader or entity possesses. A government with vast economic leverage or widespread public support holds significant political “energy.” Yet, this energy (capital) must be effectively applied to execute meaningful change; unutilized energy in physics, like unrealized potential in politics, yields no movement.

Work as Force x Displacement

Work in physics results from applying force to move something across a distance. Similarly, political power becomes tangible when force—whether ideological, diplomatic, economic, or military—is applied to create movement or societal change. The measure of successful political work could be seen in how far these efforts shake the status quo. For example, enacting legislation, securing rights, or resolving international conflicts reflect deliberate force reshaping entrenched systems. The greater the resistance (opposing force), the more power is required for significant motion.

Power as Energy Over Time

Physics defines power as the rate at which energy is expended to perform work, measured over time. Politically, this equates to the sustainability and intensity of influence. A fleeting, explosive exertion of power—a coup, a revolution, or a single military strike—may effect immediate change but often dissipates like a burst of kinetic energy, leaving instability or devastation. On the other hand, enduring political power is more akin to a steady stream of energy, enabling deliberate, constructive work over time. Leaders and nations that persistently apply their energy toward progress—balancing consistency with foresight—tend to achieve lasting impacts.

The Ethical Implications of Power Application

Metaphorically, how energy is directed and how efficiently work is performed reflect the purpose behind wielding power. A system operating solely on brute force neglects efficiency and often leads to excessive “energy loss,” just as selfish or short-sighted political power yields destruction without progress. Conversely, strategic, purposeful power maximizes the achieved changed relative to effort, producing results that benefit not just immediate stakeholders but the broader system.

Take, for example, Israel’s military actions in Gaza. Here, force may have pushed conflict away momentarily, but if the applied work doesn’t shift the larger dynamics toward peace or justice, the energy spent can seem wasteful or misdirected. On the other hand, altruistic energy, when applied toward humanitarian aid or diplomacy, impacts suffering to foster unity—a measured and enduring form of power.

Extending the Metaphor

The interplay between force and displacement also echoes global perceptions of power. Nations or leaders may exert great energy, but if their actions cause minimal change—moving neither conflict toward resolution nor society toward betterment—then the work performed appears inefficient. Alternatively, smaller, well-directed forces can yield profound results, much like a lever amplifies mechanical advantage.

Lastly, energy in physics can take many forms—potential, kinetic, thermal. Politically, power too manifests in multiple facets, from military might (kinetic energy) to diplomatic alliances (potential energy), and even “soft” influences like culture or social media (thermal energy spreading through a system). Each form requires careful management to ensure it furthers ethical and long-term goals, preventing dissipation into destructive or stagnant cycles.

By translating these physical concepts into political realities, we gain a more precise framework to scrutinize the exertion of power. Like energy, power’s value lies not in its existence but in its application—measured by the purpose it serves and the change it achieves.

Let Light and Love and POWER

restore the Plan on Earth